Understanding Reasoning Models & Test-Time Compute: Insights from DeepSeek-R1

In this article, we’ll break down Test-Time Compute and its relationship with reasoning models in a clear and engaging way. We’ll first ...

Understanding Reasoning Models & Test-Time Compute: Insights from DeepSeek-R1

This article was originally written in Chinese and translated into English using AI. If you notice any errors, please feel free to contact me.

Currently known Reasoning models, surveyed up to February 28, 2025

A new class of large language models (LLMs) is rapidly emerging — Reasoning Models, including OpenAI-o1, DeepSeek-R1, and Alibaba QwQ. Before these models, AI systems were typically designed for speed, generating instant responses. However, OpenAI’s introduction of the o1 model marked a major shift with the concept of “slow thinking.” This approach fundamentally changed expectations, allowing o1 to achieve remarkable feats — ranking 89th in programming competitions, placing in the top 500 of the US Math Olympiad qualifier, and even surpassing PhD-level accuracy in fields like physics, biology, and chemistry.

This breakthrough highlighted a key insight: when models are given time to process information and reason step by step rather than rushing to produce answers, their performance significantly improves. This phenomenon is closely related to an important concept known as Test-Time Compute.

In this article, we’ll break down Test-Time Compute and its relationship with reasoning models in a clear and engaging way. We’ll first explore the origins and evolution of reasoning models before introducing the concept of Test-Time Compute. Then, we’ll examine how DeepSeek-R1 utilizes this technique, analyze its impact and limitations, and finally, discuss what the future holds for this exciting area of AI development.

What are Reasoning models?

Reasoning models are a novel category of language models (LMs) designed to tackle complex problems by breaking them down into smaller, structured steps and solving them through explicit logical reasoning. These models, known as Reasoning Language Models (RLMs) or Large Reasoning Models (LRMs), are gaining prominence for their ability to perform systematic reasoning ( Besta et al., 2025 ) .

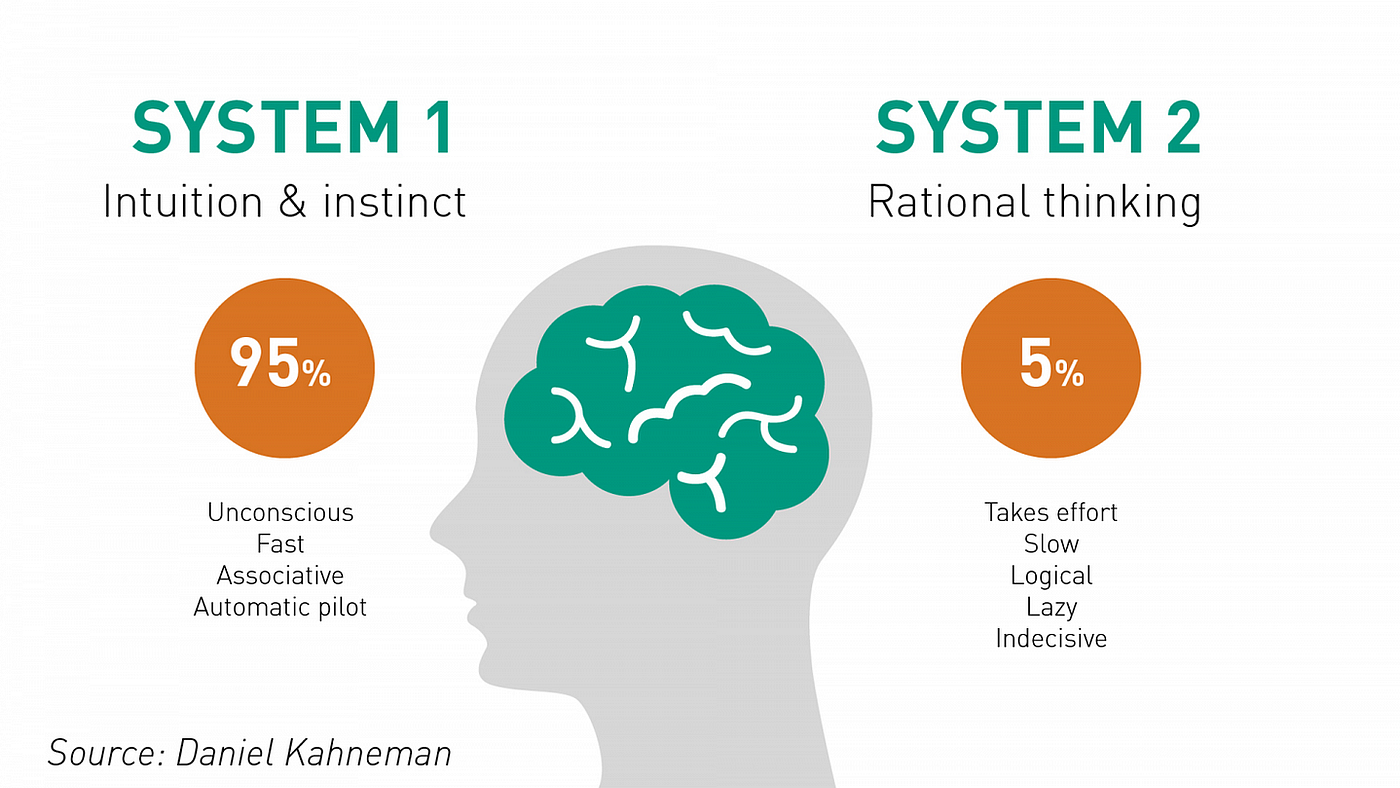

To understand the distinction between RLMs and traditional LMs, we can draw an analogy from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow , which describes two modes of human cognition:

- System-1 thinking : Fast, intuitive, and automatic

- System-2 thinking : Slow, analytical, and logic-driven

Two Modes of Human Cognition: System 1 Thinking & System 2 Thinking

For System 1 tasks , such as simple question-answering, standard LMs perform remarkably well, as they can quickly generate responses using pattern recognition — something that students using ChatGPT demonstrate daily. However, System 2 tasks , like solving complex university-level math problems, demand a structured, multi-step reasoning process. Unlike conventional LMs, RLMs are specifically designed to handle these challenges by methodically deconstructing problems and applying logical inference, making them a significant step forward in AI’s ability to engage in deep reasoning.

Origins of Reasoning Models

Following impressive System-1 capabilities demonstrated by LLMs, researchers began exploring their limitations and potential improvements in System-2 tasks. A significant breakthrough was the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) experiments proposed by Wei et al. (2022) . They found that simply including instructions like “Let’s think step by step” in prompts dramatically enhanced the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. This phenomenon was further validated by Kojima et al. (2022) , leading to more sophisticated reasoning frameworks, such as Tree of Thoughts (ToT) .

Although OpenAI’s o1 model’s “deep reasoning” superficially resembles existing CoT techniques, there is a critical difference. While CoT prompts models to explicitly articulate reasoning steps, the intermediate steps themselves remain unverified and unweighted against alternative possibilities. Therefore, even a single incorrect intermediate step can compromise the final output. Thus, CoT-like methods merely prompt reasoning at the superficial level without enabling the models to truly internalize reasoning processes.

Evolution of Reasoning Models

The foundation of RLMs remains intricate and opaque , making it difficult to determine whether OpenAI o1’s advancements stem from the model itself or rely on external systems. While its technical details are still largely undisclosed, OpenAI o1 has undoubtedly played a pivotal role in the evolution of RLMs, driven by three major technological advancements:

- Reinforcement Learning (RL) -based model design, such as AlphaZero

- Advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) and Transformer architectures, exemplified by GPT-4o

- The continuous growth of supercomputing and High-Performance Computing (HPC) capabilities

Besta et al. (2025) explore the history and evolution of RLM through three key elements.

Following OpenAI o1’s success, researchers have attempted to reconstruct its reasoning mechanisms. Studies by Besta et al. (2025) and Wang et al. (2024) suggest that RLMs may incorporate sophisticated techniques such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) and Beam Search to enhance decision-making, alongside reinforcement learning (RL) for ongoing optimization. Furthermore, Process-Based Supervision (PBS), Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and Tree-of-Thought (ToT) reasoning methods, as well as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), are considered integral to their functionality.

In the open-source domain, initiatives such as OpenR (Wang et al., 2024) , Rest-MCTS (Zhang et al., 2024) , Journey Learning (Qin et al., 2024) , and LLaMA-Berry (Zhang et al., 2024) have pursued various approaches. The following section delves into the research progress of Journey Learning.

Qin et al. (2024 ) explore the research trajectory of OpenAI o1 technology, published on October 8, 2024.

Reasoning Models and DeepSeek-R1

However, none of the aforementioned methods have matched the reasoning performance of OpenAI o1 until the emergence of DeepSeek-R1. As described in their paper ( DeepSeek-AI et al. (2025 ), DeepSeek follows the same fundamental principle championed by OpenAI o1: deep, step-by-step reasoning is essential for solving complex tasks. Their key objective was to push models to “think” more deeply during inference, leading them to explore enhancements in Test-Time Compute.

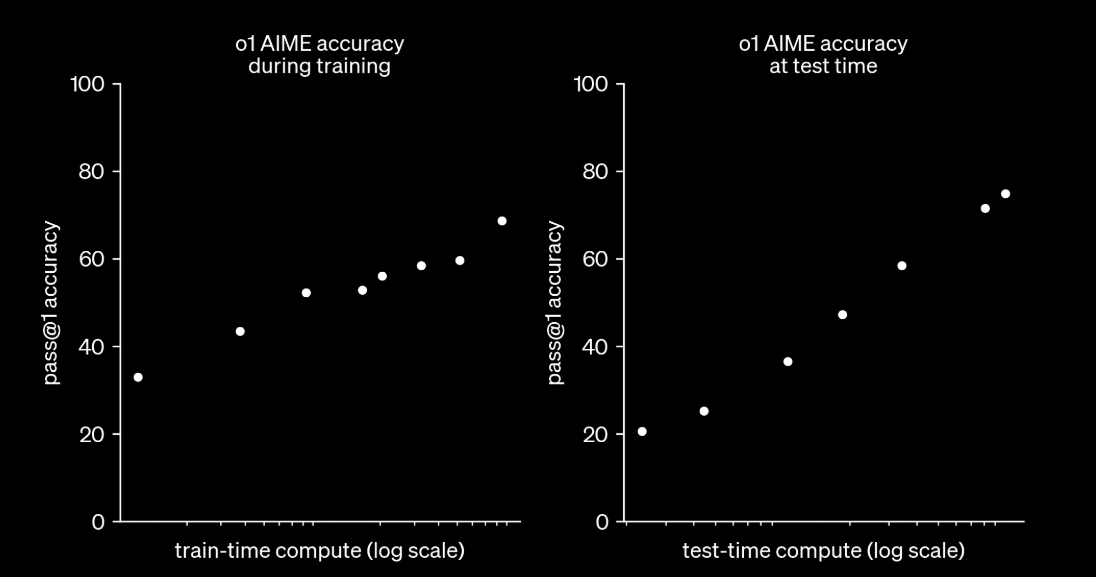

OpenAI had already laid the foundation for this approach. In their 2024 technical report ( OpenAI, 2024 ), they introduced the idea of extending inference time to improve Test-Time Compute. Similarly, research by DeepMind ( Snell et al., 2024 ) confirmed that the Scaling Law, originally formulated for training, applies equally to inference. This principle has been validated across benchmarks in fields like mathematics, physics, and chemistry, bringing AI reasoning closer to human expert cognition.

The performance of o1 improves steadily with Train-Time Compute and Test-Time Compute (OpenAI, 2024)

DeepSeek, however, brings its own distinctive innovations to model architecture and training, with a strong emphasis on reinforcement learning (RL) and Test-Time Compute extensions. In the following sections, we will explore how DeepSeek constructs its RLMs step by step. But first, we need to understand what Test-Time Compute really means.

What is Test-Time Compute?

Test-Time Compute refers to the computational resources required during a model’s inference phase — the processing power and time needed to generate responses after training is complete. More than just a technical metric, it represents a shift in how AI systems distribute computing resources .

Before mid-2024, improving the performance of LLMs was primarily driven by scaling up three key factors, a practice known as Train-Time Compute. While this approach was highly effective, the growing size of pre-trained models made training costs prohibitively expensive, sometimes reaching billions of dollars. These factors included:

- The number of model parameters

- The size of training datasets (measured in tokens)

- The computational power required (FLOPs)

Interestingly, the scaling laws that governed Train-Time Compute were found to apply to Test-Time Compute as well. Research by Jones (2021) on board games revealed a linear relationship between the two: increasing Train-Time Compute leads to a proportional reduction in Test-Time Compute.

The relationship between Train-Time Compute and Test-Time Compute across different benchmarks ( Jones, 2021 )

This discovery has led AI developers to rethink computational resource allocation. Instead of focusing solely on pre-training, more attention is now being placed on optimizing inference. By investing more in Test-Time Compute, LLMs can engage in deeper reasoning, effectively “thinking” through complex problems. This shift is particularly crucial for developing autonomous AI agents capable of self-optimization and handling open-ended, high-intensity reasoning and decision-making tasks.

How Does DeepSeek-R1 Apply Test-Time Compute?

On January 20, 2025, DeepSeek introduced three models: DeepSeek-R1-Zero , DeepSeek-R1 , and DeepSeek-R1-Distill . From the evolution of these models, we can clearly see how DeepSeek constructs its RLM.

Below is an overview of these models, illustrating the evolution clearly:

- DeepSeek-R1-Zero: Pure RL model.

- DeepSeek-R1: Initially fine-tuned with a few multi-step reasoning examples, followed by RL.

- Distillation: Transfers DeepSeek-R1’s reasoning capabilities to smaller-scale AI models, equipping them with powerful reasoning performance.

The development process of three different models in the DeepSeek R1 technical report ( Raschka, 2025 )

1. DeepSeek-R1-Zero: A Pure RL Model from Scratch

- At this stage, the model solely relies on RL to learn reasoning skills without any initial supervised data. It acquires rewards or penalties through its actions (the model’s outputs) and continuously learns multi-step reasoning through trial and error.

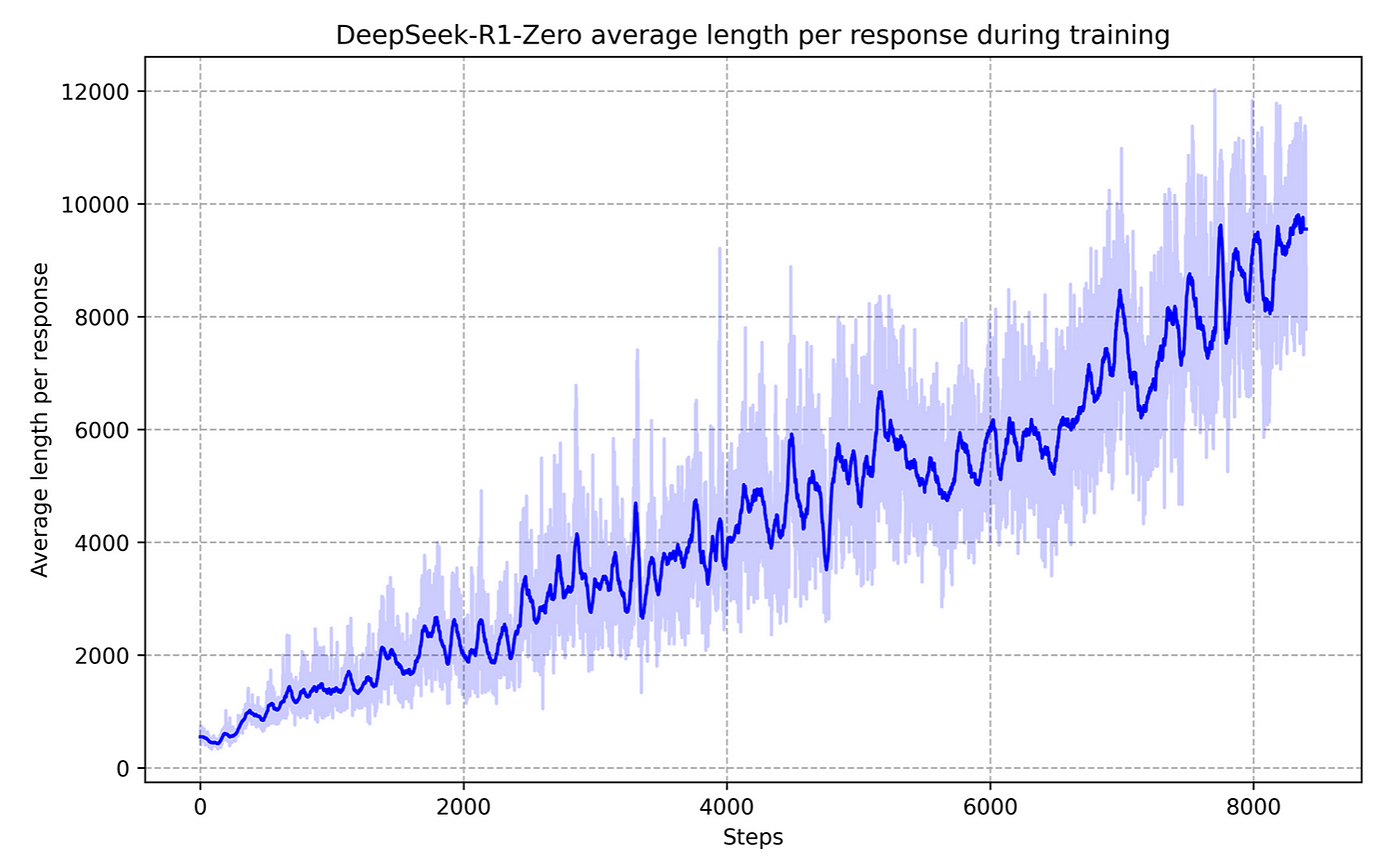

- During inference, DeepSeek-R1-Zero continuously evolves by revisiting previous thoughts, gaining deeper “reflection” capabilities as reasoning steps increase. This process, termed “self-evolution,” leads the model from producing hundreds of reasoning tokens initially to thousands or tens of thousands over time, directly translating to increased Test-Time Compute.

- While DeepSeek-R1-Zero demonstrates remarkable effectiveness in mathematics and logical reasoning tasks, it struggles with outputs prone to mixed languages and disorganized formats due to the absence of supervised fine-tuning.

- Note: The RL algorithm employed here is Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) , an improved version of PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) . GRPO uniquely does not require an additional value function model, reducing training costs and enhancing performance through action comparisons within a group and using average rewards as baselines ( DeepSeek-AI et al., 2025 ) .

The reasoning time of DeepSeek-R1-Zero continuously improves as the RL training process progresses.

2. DeepSeek-R1: Multi-stage Optimization Pipeline for Enhanced Reasoning

Due to the formatting and language mixing issues of DeepSeek-R1-Zero, DeepSeek made further refinements in subsequent models:

- Cold Start Fine-Tuning: The model is initially “warmed up” using a small number of high-quality Chain-of-Thought (CoT) examples and highly readable data, helping it quickly achieve deep reasoning without becoming unstable or divergent, laying the groundwork for subsequent multi-step reasoning.

- Reasoning-Oriented RL: RL training specifically targets fields such as mathematics and programming requiring multi-step reasoning, introducing a “language consistency reward” to penalize language mixing and promote readable, human-friendly outputs. This naturally necessitates additional Test-Time Compute, allowing deeper iterative thinking and verification for complex problems.

- Rejection Sampling + Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): After the initial RL phase stabilizes, the model generates large-scale data filtered through rejection sampling, retaining high-quality examples for further fine-tuning. This helps extend reasoning capabilities to broader applications and ensures adaptive reasoning during inference.

- Second RL Phase: Following the fine-tuning, a second RL phase aligns the model better with user instructions, enhancing both user-friendliness and reasoning accuracy.

3. Distillation: Transferring Large Model Reasoning Capabilities to Smaller Models

Given that DeepSeek-R1 contains 671B parameters , operational costs and hardware requirements are significant. To democratize its advanced reasoning capabilities, DeepSeek researchers distilled its reasoning capabilities into smaller models:

1. Distillation Training Data: 800,000 High-Quality Samples:

- Researchers collected approximately 800,000 high-quality examples (600,000 with explicit CoT reasoning steps, 200,000 general Q&A) .

- Smaller “student” models learn to replicate probability distributions produced by the “teacher” model (DeepSeek-R1) given the same prompts.

2. Learning “Reasoning Patterns,” not Just Answers:

- By aligning outputs closely with the teacher model’s distributions, the student models gradually internalize DeepSeek-R1’s reasoning strategies.

- The resulting smaller models, such as Qwen-32B, demonstrate high accuracy across various reasoning tasks while being deployable on consumer-grade hardware, significantly reducing deployment barriers.

The core idea behind this research is simple yet powerful: enabling deeper, more flexible thinking during inference — an approach known as Test-Time Compute. This journey begins with the validation of DeepSeek-R1-Zero, advances to DeepSeek-R1 employing multi-step reasoning during inference, and culminates in the distillation of advanced reasoning techniques from large models into smaller ones. By incorporating additional reasoning steps and computational resources, DeepSeek-R1 excels at solving complex problems with precision and efficiency. Meanwhile, through distillation, these capabilities are shared, allowing more developers and users to leverage cutting-edge inference technology.

Test-Time Compute is not just about extending inference tokens — it provides the model with the necessary time and resources to iteratively verify, refine, and optimize its reasoning process. This adaptability enables the model to dynamically adjust its strategies at different stages, maximizing its reasoning potential and delivering outstanding performance across multiple benchmarks.

DeepSeek’s Failed Attempts

Nevertheless, DeepSeek’s effort to enhance its Test-Time Compute capabilities has not been entirely smooth. As discussed earlier in the “Evolution of Reasoning Models” section, RLMs likely integrate multiple techniques, including Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), Beam Search, Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Process Reward Models (PRM), many of which are key to Test-Time Compute applications. In its early research phase, DeepSeek explored these techniques to enhance its model’s reasoning capabilities. However, two notable attempts proved unsuccessful:

- Process Reward Model (PRM) : Although theoretically appealing due to its capacity to evaluate the correctness of each reasoning step individually, PRM faced practical challenges. Precise assessment of intermediate reasoning steps was problematic because many reasoning tasks lack explicit intermediate standards. Furthermore, PRM frequently led to Reward Hacking, where models exploit scoring criteria without genuinely improving outcomes. Additionally, PRM required extensive manual annotation, limiting scalability.

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) : Despite its success in board games, applying MCTS to LLMs encountered exponential expansion in token-generation search spaces, causing inefficiency. Even when imposing strict limitations on node expansion, models easily fell into local optima. Although MCTS could theoretically enhance exploration efficiency in certain contexts, it proved unstable and impractical for large-scale RL training scenarios.

DeepSeek’s experience underscores an important reality: while these advanced Test-Time Compute techniques are theoretically compelling, their high computational costs, complexity, and convergence challenges often make them impractical for real-world applications. Recognizing these limitations, DeepSeek-R1 opted for a more straightforward approach to training its reasoning models, avoiding these overly intricate techniques.

Note : DeepSeek has introduced numerous other innovations, which are not covered in this discussion.

Test-Time Compute Effects on Small Models

Previously, we discussed how DeepSeek-R1 uses distillation to transfer the reasoning power of a massive 671B model to a smaller one. However, distillation is not the only method for enhancing smaller models. Research has shown that simply increasing Test-time Compute — the computational effort allocated during inference — can enable small models to outperform much larger ones, particularly in mathematical and programming tasks.

For instance, Beeching et al. (2024) reported that after 256 iterations, the relatively small Llama-3.2 3B model managed to surpass the performance of the Llama-3.1 70B model, which has over 20 times more parameters. Similarly, DeepMind’s study ( Snell et al., 2024 ) found that when additional compute was provided during inference, the PaLM 2-S small model outperformed a model 14 times its size. Brown et al. (2024) explored a different approach using Repeated Sampling, where a model generates multiple responses to the same problem and selects the best one. Their results were striking: a mid-sized model that could solve only 15.9% of problems in a single attempt saw its accuracy soar to 56% after 250 attempts, surpassing the previous best single-pass score of 43%.

Beeching et al. (2024) compare the performance of the small models Llama-3.2 1B and 3B against Llama-3.1 70B across different iteration counts.

These findings suggest an important shift in perspective: rather than solely relying on scaling up model size and training data, we should consider increasing a model’s ability to “think” more deeply during inference. Could this be the key to unlocking superior AI performance?

Limitations of Test-Time Compute

At this stage, Test-time Compute should be viewed as a complement rather than a replacement for large-scale pre-training . While increasing Test-time Compute can significantly enhance the performance of smaller models, research indicates that it cannot fully substitute for extensive pre-training. Snell et al. (2024) found that for particularly challenging problems, even when small models perform numerous reasoning steps, their improvements remain limited. In such cases, only expanding the model’s parameters and investing more in Train-Time compute can lead to substantial performance gains. In other words, Test-time Compute is only effective when the model has a “non-zero starting point” — if it lacks any prior understanding of a problem type, no amount of additional reasoning will produce the correct answer.

Similarly, Brown et al. (2024) observed that when tasks cannot be automatically verified (such as those beyond mathematics and programming), majority voting as a selection strategy eventually reaches a plateau after a few hundred iterations, showing no further gains with additional Test-time Compute. These insights emphasize the distinct yet complementary roles of Train-Time compute and Test-time Compute — Train-Time compute lays the foundation of the model’s knowledge and abilities, while Test-time Compute builds upon and enhances these foundations.

Future Directions

Since 2024, we have seen a rapid emergence of RLMs, and this trend shows no signs of slowing down. With ongoing research pushing the limits of Test-time Compute, we can anticipate even more advancements in the near future. Based on the latest studies and findings, here are some key directions that may shape the future of RLMs:

1. Hybrid Training and the Rise of RLMs

Test-time Compute has demonstrated its ability to enhance a model’s performance beyond its initial training. In the coming years, we are likely to see a surge in hybrid strategies that integrate Train-time Compute with Test-time Compute, enabling models to achieve superior performance even under constrained computational resources. This shift could make RLMs a fundamental component of next-generation LLMs.

2. Adaptive Reasoning: Smarter and More Efficient Computation

Not all questions require extensive reasoning — some can be answered instantly, while others demand deeper logical processing. Researchers are working on models that can intelligently assess a question’s complexity and allocate computing power accordingly. Future RLM APIs may introduce an “inference budget” setting or dynamically adjust the depth of reasoning to optimize both efficiency and cost, ensuring that users only pay for additional computation when necessary.

3. Balancing Quick Responses and Deep Thought

While this concept overlaps with adaptive reasoning, it focuses on the synergy between standard LLMs and RLMs. A promising direction is the development of a dual-tier AI system: a fast, conventional LLM handles straightforward queries with minimal computation, while an RLM is activated for more complex tasks that require deeper reasoning. This approach ensures both efficiency and enhanced problem-solving capabilities.

4. AI That Learns During Inference

One of the most cutting-edge research areas is Test-time Training , which blurs the boundary between training and inference. This technique allows models to make real-time micro-adjustments to their parameters while solving problems. Imagine an AI model that, like a student cramming key facts just before an exam, refines its responses dynamically based on the task at hand. While still in its early stages, this capability could revolutionize AI adaptability, making models more flexible and responsive even after deployment.

As RLMs continue to evolve, these advancements could redefine how AI balances efficiency, reasoning, and learning, paving the way for more intelligent and adaptive systems in the future.

References

Beeching, Edward, and Tunstall, Lewis, and Rush, Sasha, “Scaling test-time compute with open models.”, 2024.

Brown, B., Juravsky, J., Ehrlich, R., Clark, R., Le, Q.V., R’e, C., & Mirhoseini, A. (2024) . Large Language Monkeys: Scaling Inference Compute with Repeated Sampling. ArXiv, abs/2407.21787 .

Besta, M., Barth, J., Schreiber, E., Kubíček, A., Catarino, A.C., Gerstenberger, R., Nyczyk, P., Iff, P., Li, Y., Houliston, S., Sternal, T., Copik, M., Kwa’sniewski, G., Muller, J., Flis, L., Eberhard, H., Niewiadomski, H., & Hoefler, T. (2025) . Reasoning Language Models: A Blueprint.

DeepSeek-AI, Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q., Ma, S., Wang, P., Bi, X., Zhang, X., Yu, X., Wu, Y., Wu, Z.F., Gou, Z., Shao, Z., Li, Z., Gao, Z., Liu, A., Xue, B., Wang, B., Wu, B., Feng, B., Lu, C., Zhao, C., Deng, C., Zhang, C., Ruan, C., Dai, D., Chen, D., Ji, D., Li, E., Lin, F., Dai, F., Luo, F., Hao, G., Chen, G., Li, G., Zhang, H., Bao, H., Xu, H., Wang, H., Ding, H., Xin, H., Gao, H., Qu, H., Li, H., Guo, J., Li, J., Wang, J., Chen, J., Yuan, J., Qiu, J., Li, J., Cai, J., Ni, J., Liang, J., Chen, J., Dong, K., Hu, K., Gao, K., Guan, K., Huang, K., Yu, K., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Zhao, L., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Xu, L., Xia, L., Zhang, M., Zhang, M., Tang, M., Li, M., Wang, M., Li, M., Tian, N., Huang, P., Zhang, P., Wang, Q., Chen, Q., Du, Q., Ge, R., Zhang, R., Pan, R., Wang, R., Chen, R.J., Jin, R.L., Chen, R., Lu, S., Zhou, S., Chen, S., Ye, S., Wang, S., Yu, S., Zhou, S., Pan, S., Li, S.S., Zhou, S., Wu, S., Yun, T., Pei, T., Sun, T., Wang, T., Zeng, W., Zhao, W., Liu, W., Liang, W., Gao, W., Yu, W., Zhang, W., Xiao, W.L., An, W., Liu, X., Wang, X., Chen, X., Nie, X., Cheng, X., Liu, X., Xie, X., Liu, X., Yang, X., Li, X., Su, X., Lin, X., Li, X.Q., Jin, X., Shen, X., Chen, X., Sun, X., Wang, X., Song, X., Zhou, X., Wang, X., Shan, X., Li, Y.K., Wang, Y.Q., Wei, Y.X., Zhang, Y., Xu, Y., Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, Y., Shi, Y., Xiong, Y., He, Y., Piao, Y., Wang, Y., Tan, Y., Ma, Y., Liu, Y., Guo, Y., Ou, Y., Wang, Y., Gong, Y., Zou, Y., He, Y., Xiong, Y., Luo, Y., You, Y., Liu, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhu, Y.X., Huang, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhu, Y., Ma, Y., Tang, Y., Zha, Y., Yan, Y., Ren, Z., Ren, Z., Sha, Z., Fu, Z., Xu, Z., Xie, Z., Zhang, Z., Hao, Z., Ma, Z., Yan, Z., Wu, Z., Gu, Z., Zhu, Z., Liu, Z., Li, Z., Xie, Z., Song, Z., Pan, Z., Huang, Z., Xu, Z., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, Z. (2025) . DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv, abs/2501.12948 .

Jones, A. (2021) . Scaling Scaling Laws with Board Games. ArXiv, abs/2104.03113 .

Kojima, T., Gu, S.S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y., & Iwasawa, Y. (2022) . Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners. ArXiv, abs/2205.11916 .

OpenAI. (2024) . Learning to reason with llms . https://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms/

Plaat, A., Wong, A., Verberne, S., Broekens, J., Stein, N.V., & Back, T.H. (2024) . Reasoning with Large Language Models, a Survey. ArXiv, abs/2407.11511 .

Qin, Y., Li, X., Zou, H., Liu, Y., Xia, S., Huang, Z., Ye, Y., Yuan, W., Liu, H., Li, Y., & Liu, P. (2024) . O1 Replication Journey: A Strategic Progress Report — Part 1. ArXiv, abs/2410.18982 .

Raschka, S. (2025) . Understanding reasoning in LLMs . Sebastian Raschka’s Newsletter. https://magazine.sebastianraschka.com/p/understanding-reasoning-llms

Snell, C., Lee, J., Xu, K., & Kumar, A. (2024) . Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters. ArXiv, abs/2408.03314 .

Se, K., & Vert, A. (2025, February 6) . What is test-time compute and how to scale it? [Community Article] . Retrieved from https://huggingface.co/blog/Kseniase/testtimecompute

Wang, B., Min, S., Deng, X., Shen, J., Wu, Y., Zettlemoyer, L., & Sun, H. (2022) . Towards Understanding Chain-of-Thought Prompting: An Empirical Study of What Matters. Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics .

Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Chi, E.H., Xia, F., Le, Q., & Zhou, D. (2022) . Chain of Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. ArXiv, abs/2201.11903 .

Wang, J., Fang, M., Wan, Z., Wen, M., Zhu, J., Liu, A., Gong, Z., Song, Y., Chen, L., Ni, L.M., Yang, L., Wen, Y., & Zhang, W. (2024) . OpenR: An Open Source Framework for Advanced Reasoning with Large Language Models. ArXiv, abs/2410.09671 .

Wang, J. (2025) . A Tutorial on LLM Reasoning: Relevant Methods behind ChatGPT o1.

Zhang, D., Zhoubian, S., Yue, Y., Dong, Y., & Tang, J. (2024) . ReST-MCTS*: LLM Self-Training via Process Reward Guided Tree Search. ArXiv, abs/2406.03816 .

Zhang, D., Wu, J., Lei, J., Che, T., Li, J., Xie, T., Huang, X., Zhang, S., Pavone, M., Li, Y., Ouyang, W., & Zhou, D. (2024) . LLaMA-Berry: Pairwise Optimization for O1-like Olympiad-Level Mathematical Reasoning. ArXiv, abs/2410.02884 .

Support & Encouragement

If you found this article helpful or would like to support my work, feel free to clap for the article or buy me a coffee via the link below. Thank you for your support!

{:target="_blank"} explore the history and evolution of RLM through three key elements.](/assets/d30783070827/1*nhRPBDxaFX-6nVd5DzV5og.png)

{:target="_blank"} ) explore the research trajectory of OpenAI o1 technology, published on October 8, 2024.](/assets/d30783070827/0*cPHzQAg2b1po86PY.png)

{:target="_blank"} )](/assets/d30783070827/1*2SIIlNycBVcAkBk_bazA-w.png)

{:target="_blank"} )](/assets/d30783070827/0*LsCseumS39nkwxV-.png)

{:target="_blank"} compare the performance of the small models Llama-3.2 1B and 3B against Llama-3.1 70B across different iteration counts.](/assets/d30783070827/1*R22Ymhk78o0Dxc2plwCDdQ.png)